Poverty is looking a likely topic for testing in A-level exams in Summer 2023, especially for AQA.

In-work poverty (also known as working poverty) describes households who live in relative poverty (less than 60% of median income) even though at least one person in the household is in paid work.

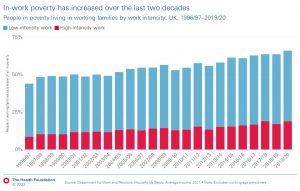

In-work poverty has accounted for an increasing share of UK poverty over recent decades. This graph from the Health Foundation shows that 43.9% of all poverty was in-work poverty in 1996/97 but by 2019/20 the figure stood at 65.9%.

In-work poverty is most common in:

- Single-parent households

- Households with children where there is only one earner

- Households where nobody works full-time

The trend of increasing in-work poverty is long established, and partly reflects the fact that more people are in work than previously, even if that work is low paid and, in many cases, part-time. There was even some reduction of the numbers affected by in-work poverty as the UK emerged from the effects of the pandemic.

However, there has been growing concern during the cost of living crisis. With inflation running at over 10%, wages have failed to keep pace. Prices of essentials have risen particularly sharply and in March 2023 food price inflation was as high as 19.4%. In their 2022-23 factsheet, the Trussell Trust reported that more than 328,000 families had been forced to use the services of their food banks for the first time in the previous 12 months. A large proportion of these families would be experiencing in-work poverty. Energy prices (gas and electricity) have also been extraordinarily high, though thankfully may now have peaked.

A little knowledge of the trend towards increased in-work poverty can go a long way in supporting exam answers, especially in evaluation. For example:

- It might be argued that there is a strong need for affordable high-quality child care (including nursery education) as a means of tackling poverty. This may enable single-parents, or couples with children, to work more hours and bring more income into the household. An additional benefit of high-quality child care is its educational value which may help to break poverty cycles. Moreover, the UK has experienced a tight labour market in the past couple of years, with firms experiencing shortages of workers, and this problem would be reduced if parents are able to supply more hours of labour. In the March 2023 budget, the government announced that working parents in England will be able to access 30 hours of free childcare per week, for 38 weeks of the year, from when their child is 9 months old to when they start school. This will be rolled out in stages from April 2024 onwards.

- The national minimum wage, which rose to £10.42 an hour for those aged 23+ in April 2023, helps to raise living standards for those who receive it. It might be argued that further significant increases in the national minimum wage are justified to help avoid more in-work poverty, especially in the context of the cost of living crisis. It’s important to balance this against concerns that higher minimum wages may be a source of unemployment, especially as many firms have been unable fully to pass on recent increases in costs to consumers, so are experiencing lower profit margins. Further increases in minimum wages may also contribute to wage-price spirals, meaning that inflation stays higher for longer.

- Low wages are a key factor for in-work poverty, suggesting that there may be a need to focus on policies to raise the productivity of workers, such as greater government spending on training to help boost skills. This would raise the marginal revenue product of workers, increasing demand for their labour and helping to boost wages. Although there is no guarantee that spending more money on training would be effective, it can be argued to be particularly important because it can break poverty cycles and tackles the root cause of poverty.